Sierra Leone’s Irish alliance bodes well for women affected by violence

Ireland is supporting efforts to tackle gender-based violence in Sierra Leone and focus greater attention on women’s rights.

-

-

Lisa O’Carroll in Freetown

- guardian.co.uk,

-

The World Health Organisation recently trained the spotlight on gender-based violence, particularly in Africa, where almost half of all women will experience physical or sexual assault in their lifetime.

For Princess Squire, a counsellor, and her sister, Annie Mafinda, a midwife, this will come as no surprise. They run a sexual assault clinic at a maternity hospital in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Last year, they dealt with 1,000 cases, predominantly rape.

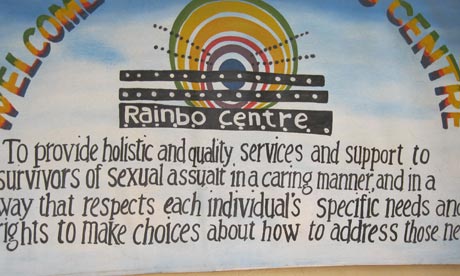

The number of people reporting assaults has more than doubled since the first of the country’s three Rainbo centres opened in 2003, reflecting a growing awareness that violence against women is a punishable crime, and that women can access treatment.

Rainbo counsellor Princess Squire with her sister Annie, a midwife. Photograph: Lisa O’Carroll/guardian.co.uk “For more and more women, there is a realisation that what a man can do, a woman can do, so they won’t accept what’s gone on before,” says Mafinda.

Rainbo counsellor Princess Squire with her sister Annie, a midwife. Photograph: Lisa O’Carroll/guardian.co.uk “For more and more women, there is a realisation that what a man can do, a woman can do, so they won’t accept what’s gone on before,” says Mafinda.

Historically, the tolerance ofgender-based violence in Sierra Leone has been high. Cultural factors have shaped this trend, but efforts to shift attitudes were boosted in 2007 when, in one of three gender-related acts of parliament passed that year, domestic violence became a crime.

Ireland, which recently made Sierra Leone one of the nine key partner countries for Irish Aid, has singled out gender inequality and associated issues for long-term attention, focusing on rape crisis centres and strengthening the judicial system.

If reporting sexual violence is the first link in the justice chain, then the number of women passing through the Rainbo centres, which are funded by Irish Aid, is a measure of success.

But according to Sinead Walsh, the Irish chargé d’affaires in Freetown who oversees the country programme, creating a structure for reporting violence isn’t enough in a republic where the judicial system had been decaying for decades even before the civil war. If the police, courts and civil service are not working together, all efforts are “handicapped” from the outset, says Walsh.

This is one reason why Irish Aid is spending part of its €2.1m (£1.7m) investment on Saturday courts around the country to deal exclusively with women, as part of a bid to reduce the backlog of cases.

“We started funding this last November because we were seeing a situation where the Rainbo centres were providing access to courts, but if the courts were not functioning well, we were leaving these women at a loss,” says Walsh.

The scheme, which is part of the UN’s improving the rule of law and access to justice programme, also involves monitoring and documenting the courts to help bed down procedures, and paralegal training for local community organisations to enable them to make interventions if due process is not being observed. In addition, standard operational procedures for police and training for 200 officers are being developed.

Yet this is the bare minimum to get rape and sexual assault treated with the seriousness they warrant, Walsh reiterates. “Three gender acts [were] passed in 2007, which is terrific progress, but their implementation is limited. It can often be something as simple as police not having the cars, trained personnel, [or even] the paper to do photocopies. That is why, when an act is passed, it is important that everyone sits down together and assesses what is needed to make it work.”

One of the biggest challenges, says Walsh, is the lack of a skilled workforce. “There is a huge gap of skills in the civil service. You have some very strong people at the top and a huge amount of people at the lower level, but there is a big missing middle.” The civil service as a whole has a quarter of the professional and technical level staff it needs, according to a recent World Bank study.

“We are enormously optimistic in the Irish government about the potential in Sierra Leone,” says Walsh. “The government is doing a lot, donor co-ordination is strong, including a close group of four EU donors. Everybody is working together to rebuild the country.”

Since the war, huge strides have been made in Sierra Leone. Stability and development have improved, and the economy is booming. The important thing, says Walsh, “is to focus in on the sometimes neglected issues such as gender equality and women’s rights so that nobody gets left behind in the country’s progress and everybody can contribute to building the future of Sierra Leone”.